This summer, my wife and I decided to refurbish our second floor bathroom that the previous owners, a family from Milan, had fitted out in the mid-1980s with classic black and white tile and a shower stall. 11 years without a bathtub, we reasoned, was long enough.

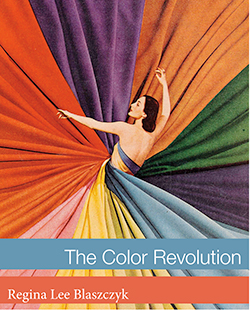

- The Color Revolution by Regina Lee Blaszczyk. 400 pages. The MIT Press. $34.95.

Seeking ideas, we turned to our well-worn copy of the 1996 In Town, by the London interior designer Tricia Guild, whose design approach celebrates the color and texture of the city. “The streets are full of inspiration for using color in the urban home,” writes Elspeth Thompson in the book’s introduction, and indeed, Guild’s philosophy had been our inspiration when we renovated our first house, a rustic 1840s Philadelphia double-trinity, in 1998. At Guild’s London townhouse, Thompson explains, “seldom is color seen as a flat, inanimate surface. The walls vibrate with flat swirls of pure pigment sunk into the raw plaster as it dried, or flash with the glint of thousands of tiny mosaic tiles in cobalt blue, lime, or orange.” And so for our bathroom, we would reproduce the wall of lime green mosaic Guild had used above her guest bath.

The only problem: No one carried lime green tile. The only greens in the countless showrooms we visited were muted ones — variations on sagebrush and sea foam. Lime green was out of style and off the shelves.

We eventually found our tile through an Internet dealer — this is the age, to paraphrase the architect Louis Kahn, of availabilities, when you can purchase a remake 1977 cherry red plaid suit in a high fashion shop on Filmore Street in San Francisco just as you can acquire a circa 1952 tangerine colored Bertoia Bird Chair in the store next door. But our lime green letdown points to a system of color management that blossomed in the early 20th century and is the subject of a exhaustively researched and beautifully illustrated book The Color Revolution by the industrial historian Regina Lee Blaszczyk.

“In 1923, when Ford was still making its somber Model T,” she writes, “General Motors introduced the two-tone Oakland. A year later, the Curtis Publishing Company introduce the first four-color advertisements… In 1926, the New York retailer R.H. Macy and Company launched a “Color in the Kitchen” promotion, offering brilliantly colored housewares.” A few years later, notes Blaszczyk, Fortune called it “the color revolution.”

An expert on the iterative process of taste-making that occurs between producers and consumers, who along with her husband decorates and redecorates the façade of her Philadelphia house in bright, exuberant colors according to holiday or season, Blaszczyk seeks in this book, her seventh, to understand how the manmade world was transformed from relatively muted to so abundantly colorful that it would require standardization and regulation.

Color management, she writes, “was a fiercely nationalistic pursuit, a child of the Second Industrial Revolution and the quest for cultural authority among inventors, innovators, and users in France, Britain, Germany, and the United States… American industry identified color as inexorably suited to mass production, and adapted it as one of its principal design tools.”

Blaszczyk’s story is the insider’s account of the innovators and style-makers (often in Paris) and their bosses who seized on chemistry, up to the minute market research, and the desire for profit to elevate color — and therefore the surface of things — to become a valuable thing in and itself. “Color is one of the most influential factors in the saleability of products,” said the silk dealer Ward Cheney, “and we must pay attention to it whether it is represented in the color of motor cars or… the package of cigarettes.”

“Like DuPont and General Motors,” explains Blaszczyk, “Cheney Brothers had accountants that analyzed weekly sales statistics. They produced a color index that showed the ‘relative popularity of the various color families, the relative movement of novelties and staples, and the individual importance of the leading novelty colors’.”

The history of color is notoriously difficult to tell because it necessarily involves questions of human perception, ambiguities of light and matter, and technical descriptions of scientific and alchemical processes. The historian has to place the shifting understandings of these elements within the contexts of culture, economics, and politics. In the edifying Bright Earth: Art and the Invention of Color, the British science writer Philip Ball leaps bravely back and forth across time and place — from Yves Klein to the ancient Egyptians to Goethe — confidently injecting his own voice to pull the reader along.

Blaszczyk skillfully allows the narrative to unfold in the hands of a set of protagonists mostly unknown to the lay reader, inventors like the British William Henry Perkin, theorists like the French Michel-Eugène Chevreul and the American Albert Munsell, who sought to create a standardized palate, the color engineer H. Ledyard Towle, a camouflage expert who showed DuPont how to exploit color for mass profit, businessmen like Cheney, the fashionista Margaret Hayden Rorke — “America’s chief chromatic officer” — and Joseph Urban, who used color as a primary force of modern architecture.

Both Ball and Blaszczyk trace the color revolution to Perkin’s discovery that a durable purple dye could be synthesized from coal waste. Unlike color derived from mixing natural pigments, synthesized color wouldn’t muddy or quickly fade, and ultimately it could be made in any shade. Perkin was a student when he made the discovery. Eschewing further scholarship for the more concrete and profitable work of marketing his inventions, he came to epitomize the protagonist who would shape the emergent world of color: intensely practical, persistent, and opportunistic.

One of the joys of reading The Color Revolution is experiencing Blaszczyk’s enthusiasm for her characters — the reader senses Perkin’s pluck, Towle’s mad joy over the psychological power of color, and Rorke’s utter persistence in pushing for industry’s adaptation of a color standard.

But in the focus on people and their various design fields, Blaszczyk gives up some of the historian’s power to connect events through the connective tissue of time. A different way of telling the story of the color revolution would have been to start with the year 1876, when in Germany Adolf Baeyer and Heinrich Caro perfected the production of cheap synthetic indigo, profoundly altering the global dye business. In London that year, chemist Otto Witt discovered a process by which the properties of synthetic colors could be predicted. “Colors could — at least, this was the hope — be manufactured to order,” writes Ball.

Blaszczyk notes that at that year’s Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, the first American world’s fair, exhibitors from around the globe produced colorful trading cards for children, whetting their “chromatic appetites.” At the same time they were walking through vast buildings designed by the engineer Herman Schwarzmann, who used color to create what, 56 years later, the modernist Joseph Urban would call “a polychrome festival.” And meanwhile a few miles away, fair visitors were among the first to discover the newly opened Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, designed by the firm of Furness and Hewitt, inside and out perhaps the most colorful building in the western world. A poem written in honor of the new art school and museum went like this:

Away with dingy neutral tints, this eager artist cried

Give me instead the rainbows here, with thunderclouds beside,

A blinding flash of lightning here, a crimson peacock there,

Pile on the color, make it bright, and let the people stare.

Blaszczyk, I sense, made the choice to tell her story chiefly through people because history so often obliterates the product designer, the middleman, or the bureaucrat. In a certain sense she believes this is the real history — and it involves all of us as consumers. Still, I would have preferred to have her frame some of the guiding moments and the tensions in a story that’s full of conflict — what revolution isn’t? — more clearly, particularly what she quietly calls “the uneasy marriage of standardization, free enterprise, and fashion.” This tension helps define our consumerist world and lies at the heart of the color revolution.

In resolving the tension, Ball concludes that ultimately it’s “futile to be dogmatic about color.” In other words, despite industry’s enforcement of color trends, someone will always keep making lime green tile. You just have to work a little to find it.

• 7 January 2013